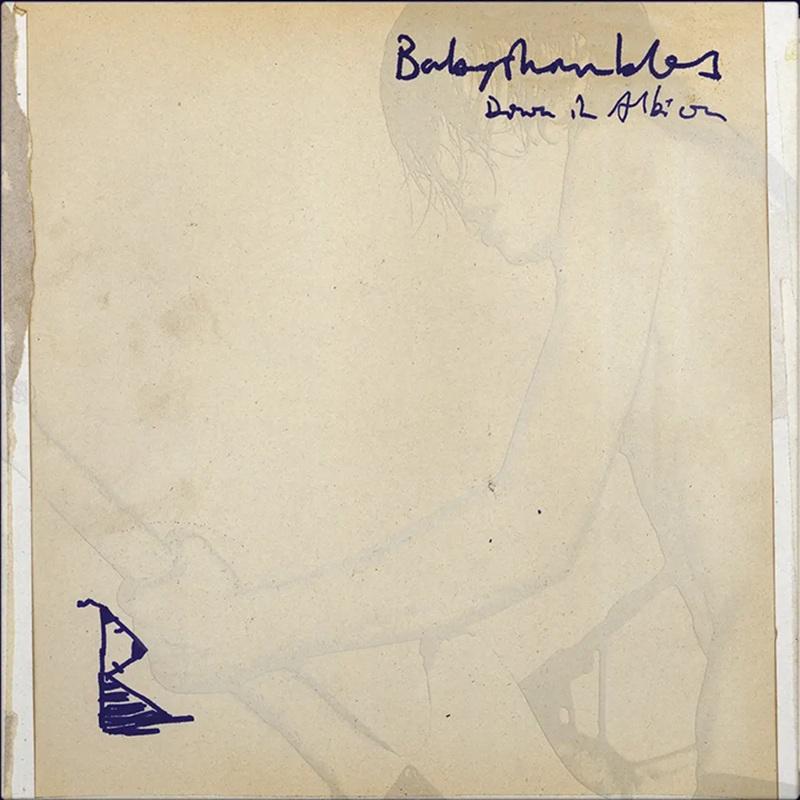

What the critics both personal and musical failed to understand was that any Babyshambles fan willing to idolize Pete Doherty’s contrivances had no desire for it to make sense anyway.

It’s very easy now, with two decades of hindsight, to be unaware of the absolute shitstorm into which Down In Albion was introduced to the world.

Excuse the profanity, but there simply isn’t a better metaphor for the chaos surrounding both it, Babyshambles even as an idea, and especially Pete Doherty.

Thrown out of his own band for infamous public issues with drug addiction, the self-styled urchin/minstrel was demonized by the tabloids in much the same way as Amy Winehouse, his relationship with model Kate Moss a turbulent and similarly doomed one.

Babyshambles conceptually began when other Libertine Carl Barât decided enough was finally enough; Doherty by turn was however still writing and seeking an outlet, with early members effectively joining a pick-up band to support him live.

Somehow, a line-up featuring Patrick Walden, Drew McConnell and Adam Ficek coalesced and, despite the arrests, cancelled tours, fall outs and sense that everything was one bad batch away from disintegration, the bones of Down In Albion began to emerge from its own druggy miasma.

Key to any chances of it getting over the finish line was the choice of producer. Here, Mick Jones was selected, ostensibly because of a heritage in Britain’s most famous punk band, but the former Clash man instantly recognised that rolling the tape would be the limit of what he could control.

Any other approach would’ve been the ultimate fool’s errand. The conditions which had driven Barât crazy still existed, the album’s body being haphazardly thrown together from Doherty’s old sketches, fresh-ish egotistical junkie tales and in Albion a former Libertines favourite.

Example? Take Pentonville, the lilting-reggae number co-written with General Santana, a former prisoner who was with the singer during his stay in the prison of the same name.

It’s a perky enough number, letting everyone know that jail has its downsides even if the fine line between voyeurism and the grisly lived experiences for those non-celebrities caught in its cycle is a blurry one.

Fuck Forever was at least more direct; jagged and basic, its demo level quality and live-fast-die-young attitude made for a parent-baiting experience all round, whilst the biographical Pipedown was a smeary, bleary exercise in self aggrandizement nowhere near as risky as it thought.

This was Down In Albion’s conceit; everyone including Doherty realized he wanted to be cherished for his flaws, not punished for them.

Equally, there’s a twinkle in his bloodshot eyes which is hard to forgive, as the groovy retro flourishes of A’rebours and Kilimanjaro’s strung out but superior indie were cast iron evidence of.

What the critics both personal and musical failed to understand was that any fan willing to idolize the singer’s contrivances had no desire for it to make sense anyway.

The record’s centrepiece, Albion, had all the coding you would ever need, with a ragged hero in an alternate country betrayed by his past, namechecking in turn distant places which he liked to think had been, like him, similarly bulldozed by progress.

Whimsy wasn’t to be checked at the desk then, but the Moss-featuring opener La Belle et la Bête has a weirdly admirable sense of bruised, skeletal devotion, The 32nd Of December’s soul is positively uplifting and What Katy Did Next’s doomed romanticism remains beautifully lost.

This anniversary edition comes with some extra stuff, they all do, but the real quiz is the same as it was two decades ago, except now it’s minus the shitstorm.

Is/Was Down In Albion a dismal failure, or a work of genius from a man whose neck felt like It was inside the noose?

Even now, it’s impossible to know.