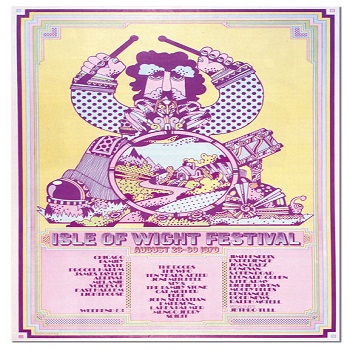

As the 1970 Isle Of Wight festival celebrates its 40th anniversary this week, we take a look at an incredible five days which, amidst the clash of hippy ideology, establishment and near-bankruptcy, came to define the shift of power from fans to business and the beginning of big-budget festivals.

“We put this festival on for you bastards, with a lot of love. We worked for one year for you pigs. Now you wanna break our walls and you wanna destroy it? Well you go to hell!”

The unforgettable words Master Of Ceremonies Rikki Farr barked out to the hundreds of thousands who had descended on the Isle Of Wight in the summer of 1970, as the conflicts between organisers and a section of the crowd looking to impart their own convictions on matters reached boiling point with proceedings in full swing. The beliefs and care-free attitudes of the day, which they had hoped would be encapsulated by that year’s Isle Of Wight, had been crumbling around the management as what was supposed to be a celebration of music and freedom for the largest gathering of people at a music event in history was instead becoming a nightmare of police regulations, money problems and lack of organisation.

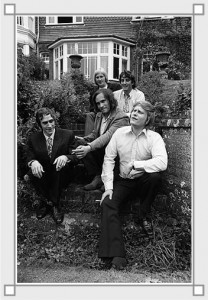

The Foulk Brothers: Ray (front left), Bill (centre), Ron (front right), with Rikki Farr (back). Photo: Peter Bull

After its modest beginnings in 1968, the Isle Of Wight festival had quickly gained a worldwide reputation when an estimated 300,000 people attended the event in 1969 thanks largely to lead promoters Ron, Ray and Bill Foulk securing the services of Bob Dylan and The Band despite the legendary Woodstock festival taking place on Dylan’s doorstep at the same time in New York that year.

Its growing status as a Mecca for those who believed passionately in the era’s hippy counter-culture – which had evolved from the previous decade’s civil rights, anti-war and free speech movements – meant numbers in 1970 were expected to surpass even the total who had attended in 1969. After just two years, chiefly thanks to the incredible coup of booking Bob Dylan, the curators had turned Isle Of Wight into an internationally recognised occasion, and despite already attracting crowds which exceeded the population of the small island itself, they were determined to make 1970 the biggest musical gathering the world had seen.

The first major headache for the Foulk brothers was to find a suitable site for the upcoming occasion. They were well aware of the problems that would be met if they chose an area surrounded by high ground and searched in vain for the perfect location having being blocked by the local council from using their previous grounds due to strong opposition from residents.

In the end, with time running out and in desperate need of land, they were forced to accept the one venue the authorities would allow them to use – East Afton Farm. It was no coincidence that this particular place was about as troublesome a location as could have been chosen, and the council had handed them the keys to a region which would present ideal opportunities to those intent on travelling to the Isle Of Wight in search of a free week’s music.

After being overwhelmed by numbers a year earlier, the leaders hoped they would leave nothing to chance in 1970, and had spent almost as much on providing adequate facilities for those in attendance as they had for booking the bands themselves. The new amenities anticipated a larger gathering than in 1969, and they hoped everything was in place to turn the Isle Of Wight into a long-term, viable celebration. As they said at the time: “We want this to become an annual event. We want it to last.”

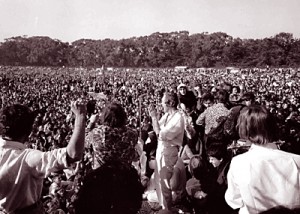

The ideal views surrounding the farm

Unfortunately for the promoters, the actual number of people intending to travel to the island that August dwarfed even the most outlandish estimates, and it would prove to be impossible to control the influx which would ultimately more than double the population of the entire island itself in just a few days. To make matters worse, a significant percentage of those travelling were doing so without a ticket.

For many of the ever-growing number of promoters in the UK and US, the initial view of free festivals was already going out of fashion. Traditionally seen as an opportunity for artists and fans to come together and promote their shared doctrines based around equality and anti-consumerism, this notion was now giving way as planners began to compete for the services of the biggest acts of the time, bowing to new pressures from agents to pay outlandish prices for their most valued bookings.

On top of this, these free carnivals were beginning to be seen not as place of peace, but of a haven for troublemakers following a series of setbacks, most notably at the now infamous Altamont Free Concert which particularly highlighted the problems being faced by the curators, as these events moved into mainstream society and began to attract congregations of a size no-one had anticipated a few years earlier.

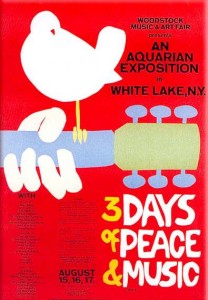

In 1969, the organisers of Woodstock had faced similar problems, having being forced to move from their own desired location not long before they expected the first arrivals. In fear of violence around their fencing perimeter, and with reports of fans carving out sections upon arrival, they took the decision to pull down the restrictions and allow freedom on to the site. It was a move which could have lead to financial ruin, but it also helped to pass Woodstock into folklore, and continued the tradition of freedom for fans.

In 1969, the organisers of Woodstock had faced similar problems, having being forced to move from their own desired location not long before they expected the first arrivals. In fear of violence around their fencing perimeter, and with reports of fans carving out sections upon arrival, they took the decision to pull down the restrictions and allow freedom on to the site. It was a move which could have lead to financial ruin, but it also helped to pass Woodstock into folklore, and continued the tradition of freedom for fans.

The Phun City Free Festival had also been held just a month earlier in England, and various underground groups who had been in attendance, including members of Hell’s Angels looking for another stint of security work, were now moving on to the Isle Of Wight expecting much of the same.

Despite the pressure, the Faulk brothers stood firm against the ticket-less travellers, and began to face some of the predicaments which had been anticipated at Woodstock a year earlier. The retention of the barricades secured the contrasting views of Woodstock and Isle Of Wight, with the former being looked back on as the peak of ‘hippy fun‘, and the latter being seen as one the symbols of its demise.

Of course, it is important to remember the majority of the near 600,000 people in attendance were there to enjoy a week of music and freedom with friends just like so many people do today. A significant section had no intention of paying, but for a large portion of them, the social impact now synonymous with the festival would no doubt have seemed like nothing more than an inconvenience being played out on the periphery. It was the vocal minority who would make that year remembered for what it is now, and who etched it a permanent place on the British, and worldwide, musical landscape as they looked to force their soon to be outdated dogma on the celebrations.

By the time proceedings were officially opened on Wednesday, 26th August by the prog-rock group Judas Jump, a new community had already made its home around East Afton Farm’s enclosures. ‘Desolation Row’, as it became known, was being frequented by some radical groups and anarchists from all over Europe, alongside those who simply expected unimpeded access, and who had thought their outlook on music and life was still mirrored by those who were both promoting, and performing at these mass get-togethers. The groups in Desolation Row quicly began to focus their ire on a management who were now encouraging them to move away from their new locality with increasing force.

At the time of the famous Summer Of Love three years earlier, artists willingly presented themselves as spokesmen for the peace and anti-establishment movements which were the backbone of the time, and were happy to stand by side with their fans. Free festivals were seen as an opportunity for those bands to give something back, and they became a very important icon of the unity felt between the two groups. Now, these fans’ ideologies were being dismissed before their eyes and, to them, the very bands who championed their beliefs just a few short years beforehand were now instead standing alongside the system they despised. As a consequence, they centred their frustrations on the organisers who they felt were pandering too easily to the demands of bands and their agents instead of concentrating on what they felt should have been the priority – the fans themselves.

Hippy fun - Human Be-In, 1967.

Tensions were growing day by day, and the increasing struggles of the Faulk brothers still trying to put on a stable event, and the resentment of sections of the crowd who were not getting what they expected (to say the least), was fuelling a darker atmosphere. The almost innocent approach of the curators flying in contrast to the mindset of those in Desolation Row is probably best summed up by an idea to attempt to engage those off-site whilst trying to diffuse some of the growing anger at the same time.

The decision was made to provide cans of paint and brushes to the groups, in the hope that they would decorate sections of the fencing that they had made their home beside with positive messages. Instead, to the consternation of the planners, the campers used the opportunity to cover the walls with nazi symbols and anti-establishment propaganda, leaving the barricades in a worse condition than when they started, and forcing the promoters to cover over the new graffiti at their own expense.

Soon, the management were feeling the pressure from the authorities as well as the fans. Not long in, Rikki Farr was asked by the police to announce their idea of a drug amnesty, where anyone aged 17 or under could hand in their drugs without fear of prosecution. The disdain with which the message is articulated was matched by those it was aimed for, and soon after Farr is found giving his thoughts on the fact that not one person had elected to take up the police’s kind invitation.

The meddling continued and other unwelcome distractions included a visit by health officials who were alerted to the rather rudimentary conditions of the toilets; drug amnesties and toilet checks were not exactly what was expected by the masses, and added to the feeling from some that the organisers had their priorities all wrong.

Leonard Cohen @ Isle Of Wight

So amidst all this, what of the line-up itself? The huge ambition of the festival as a whole is certainly reflected in the bookings, a fact which would again cause trouble for Ron, Ray and Bill as they struggled to meet the fees demanded by the scores of acts due to play over the next few days.

The line-up is impressively eclectic, if at times inconsistent. The bill contains some of the true stars of the day, some of whom were entering the peak of their careers, such as Joni Mitchell, Joan Byez and Leonard Cohen, and who were seen as the closest representatives of their generation.

Many of the stand-out performances did indeed come from these artists. Joni Mitchell delivered a note-perfect set on the Saturday afternoon, and was one of the first acts to directly address the crowd on the conflicting mood which was simmering after her performance was interrupted by a hippy reportedly named Yogi Joe, who was intent on delivering his thoughts on the unfolding story manifesting on Desolation Row to the audience. After settling the masses, Joni Mitchell closed the set with her classic ‘Big Yellow Taxi‘ to a warm response from spectators.

Another much-talked about set came from US songwriter Kris Kristofferson, who was one of the first acts to perform on the first official day. His set suffered from teething problems, and a large number of onlookers were unable to hear his music. The attempts from the audience to get the sound fixed, combined with the growing dis-quiet being heard from the fringes of the site, convinced him to leave the stage prematurely, after he mistakenly believed he was being jeered.

The Doors were onstage on the Saturday evening, but failed to match the mood of the event (or matched it perfectly, depending on your location), with frontman Jim Morrison performing the entire set in near total darkness. Despite that, the class of the band is still obvious, and it was another real plus for the festival to deliver one of the most important groups of the era. Later, the wide-ranging make-up of the bookings was highlighted by an enchanting display from one of the true legends of jazz, Miles Davis.

The highlight of the week was undoubtedly The Who, who took to the stage on the Saturday evening to deliver yet another spellbinding performance. By August 1970 the band were busy cementing their reputation as one of the greatest live acts of all time, as Pete Townshend’s ever evolving songwriting helped the boundless talents of the four members to grow into a deafening wall of noise which was virtually unique at the time.

Their first rock opera, ‘Tommy‘, had been released a year earlier, and had helped to showcase the expertise of The Who during this period which meant it was almost impossible for them to fall flat live. At Isle Of Wight, they were undoubtedly at the top of their game, and delivered one their most powerful and memorable sets. In doing so, they handed the Isle Of Wight what any major event of its kind needs – a defining performance.

Another defining moment of a different kind, and one which also helped to create the legend of the festival, came on the final day of the event when Jimi Hendrix made his last UK appearance before his tragic death less than a month later. Hendrix is often recalled as being off his game, with plenty believing some of the problems which are said to have led to his death being already apparent on the stage that night. Certainly Hendrix wasn’t helped by the massive expectations following his seminal show at Woodstock a year earlier. As the 1970 Isle Of Wight and Woodstock festivals are often compared, it’s quite fitting that Hendrix’s contrasting fortunes offers a perfect metaphor for the highs and lows experienced at the two events.

As affairs drew to a close, sections of the fencing were eventually breached by the relentless onslaught from those gathered on Desolation Row. After nearly a week of constant protestations, Rikki Farr publicly admitted there was now no chance of them generating anything near a profit, and ordered the fencing to be pulled. Finally, Desolation Row had got the free festival they desperately wanted.

Policing at the fencing

Despite threatening to cancel the whole event on more than one occasion, arguing with agents over the phone on the subject of fees, and scrambling together every last penny from punters who were willing to pay at the gate, the Faulk brothers had managed to deliver a full roster, and did indeed get their premiere acts up on stage. On the Sunday night, providing another link between Isle Of Wight and Woodstock, Richie Havens, the man who had opened Woodstock in July ’69, brought proceedings to a close.

So should the Faulk brothers have made the same decision as Woodstock had under duress in order to avoid the trouble which they subsequently encountered? There’s no question if they had done so the legacy of the event would have been very different. Financial ruin was virtually unavoidable once the council had forced them on to East Afton Farm anyway, and they may have prevented a lot of the struggles if that fact had been accepted earlier. What must be remembered however, is the crowds gathered on the Isle Of Wight that week had far exceeded anything seen anywhere in the world at the time. No-one could have anticipated just how popular that year would prove to be – the inexperience of just a handful of people could never have controlled the vast numbers from a wide-section of society who were on the island that week.

Today, most festivals have grown into huge money-making monsters, with punters routinely forking out hundreds of pounds over a weekend on tickets, food, drink and merchandise. Back in 1970, as the thousands descended on the Isle Of Wight, they were still seen as hugely important cultural events, and ones which should belong to the youth of the day. Yet, by the time the five days had been completed, it had become painfully clear to those still clinging on to the various philosophies of hippy culture that the shift to the commercially dominated events we recognise now was both well in motion and unavoidable. The aims which had led to the first music festivals, when amateur organisers had bands playing out of the back of lorries to just a small group of people, were giving way to big business and huge salaries. Now, power has been shifted to agents out to get the right price for their clients, and to the rules and regulations of police and safety authorities which are needed today.

As the dust settled it had become clear that before the familiar, slickly-run modern operations, where hundreds of people work tirelessly to ensure the smooth running of events which have less than half the numbers the Faulk brothers had to contend with, a festival on the Isle Of Wight was always going to be a short-lived venture. Instead of heralding an annual mass gathering of music lovers, those waving goodbye to the Isle Of Wight in the August of 1970 would probably never be back – it would be over thirty years before the island again hosted another music festival.

During that inimitable week, the Isle Of Wight had managed to encapsulate the hope and optimism of the Sixties making way for the harsh realities of the real world as the Seventies arrived. As it turned out, the numerous stories which were played out over the course of the festival could not have better summed up the crushed dreams of a section of those who made the trek to the Isle Of Wight on that hot August week forty years ago.

(Dave Smith)

Nicely written and researched.

Hats off, Dave, what a superb essay.

I went to the Isle of Wight on that “hot summer” when I was 15, by myself, escaping from my old -and creepy- landlady, back in London, where I attended an English language course.

I stayed there for the first 3 days; unfortunately I missed the legendary (and soon to die) Morrison and Jimi, among other icons. Nevertheless, the Isle has been one of my life´s pivotal experiences. A hug from Mexico City….

It is ok, you failed to mention more alternative acts that captivated the audience, you should have added someting about Tiny Tim and the great synchronicity moment that happened with the blue ballon. That moment has become an iconic episode for all the 1970s crowd.

jim morrison isle of wight 1970 I have a picture lp of jim’s interview can anyone tell about this lp plz

cheers Linz

Nice article. Brought back many fond memories. One point to add. Kris Kristofferson wasn’t mistaken in believing he was being jeered. Unfortunately he was being jeered, and sadly I was one of the thousands who jeered him. Basically he wasn’t very good on that occasion, and a pretty poor ironic song called “Blame it on the Stones” was the last straw. Happily he was given another set on the Sunday!

It is the words of Leonard Cohen’s about not yet being strong enough to have a revolution, how right he was given today’s BLM news.