This has been coming – Damon Albarn has been opposed to Brexit from the off.

Back in 2016, on the day after the UK’s EU referendum vote, he was at Glastonbury performing with The Orchestra Of Syrian Musicians and addressed the subdued crowd: “Democracy has failed us because it was ill informed,” he said.

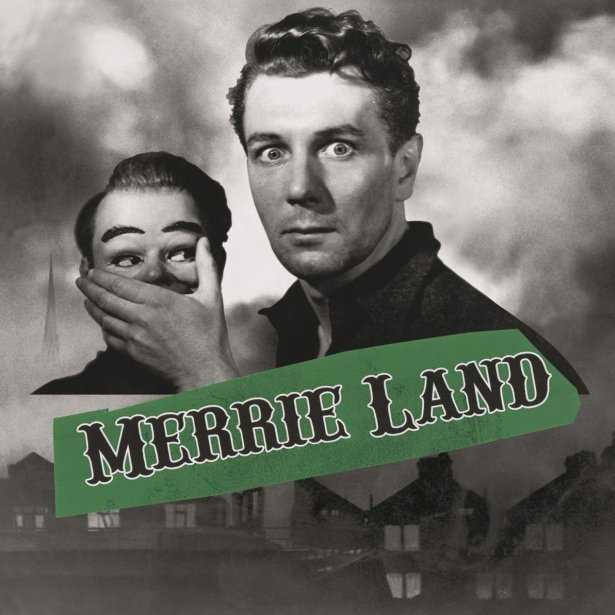

A reformation of The Good The Bad & The Queen (back in 2007 it was ambiguous as to whether or not it was a band, an album or a project – now we know) was the most likely of his various platforms to be an outlet for his thoughts on the subject.

Whereas the first album was very London-centric, Merrie Land takes in a national perspective, Albarn observing the working men’s clubs, the green distance between towns and the fairgrounds. The album is peppered with the sound of attractions, from the hurdy-gurdy swirl of the title-track to the buzzing electricity on Nineteen Seventeen, which is unsurprisingly a lament to the impact of war. It’s the key track on the album; the Great War is the UK’s annual nostalgic indulgence, but Albarn makes the point that it’s perhaps partially responsible for what he describes incredibly accurately as our current ‘Anglo-Saxon existentialist crisis’.

With that in mind, the album couldn’t be better timed, coming as it does in the week of remembrance and also what one assumes is a key stage in the Brexit process. At points, most notably on The Great Fire (‘Tuesday nights at Tiffany’s, cocktails please nurse’) he’s quite scathing and will likely rub some listeners up the wrong way. Although the title-track has the caveat of ‘this is not rhetoric, I love this country’, he’s on thin ice, but then if you step back from the B-word, the album is much more of a lament than condemnation.

Any lyrical reference to leaving or goodbyes are initially construed as departure from the European Union, but looking beyond that it could just as easily be the classic British trait of looking at the past through rose-tinted glasses. It’s also not coincidental that his singing, so under-rated but a key component of whichever tone he’s trying to evoke (throughout his career), is much more akin to late 90s Blur than anything else he’s produced recently.

So dominant is the theme of the album that it sometimes blocks out the musicianship. Two other legendary bands are represented, with Paul Simonon’s subtle bass a far cry from anything he did with The Clash and while Simon Tong’s guitar seems comparatively low in the mix, he’s as important to the chemistry as he was when in The Verve. Simonon holds the album together, his work on The Truce Of Twilight being used as the beat rather than the bass, giving free reign to the legendary Tony Allen, who it’s fair to say wasn’t used to full effect on the first album. He’s given much more to do here with his shuffling, slinky drumming managing to appear both inessential and impacting on every song. Not only that, but the legendary Tony Visconti is on producing duties – it’s surely his influence which inserted the variation of nuance that rewards multiple listens.

And there is a lot going on musically: The Lady Boston features a choir that seems a carryover from Albarn’s past operatic, specifically the Dr. Dee project which is a spiritual forebear of this album, while Drifters And Trawlers has a ska beat held together once again by Allen’s sublime drumming. The Truce Of Twilight has a full brass section, as middle-ages English flute rears its head time and time again. It’s a very visual album, the imagery of fallow fields, white crosses and maypoles leaving very little to the imagination.

It’s not quite as essential as the first album; no song matches the wonder of Kingdom Of Doom. Ribbons is the closest relation to the sublime Green Fields and indeed opens in almost exactly the same way. It’s beautiful in and of itself but doesn’t quite hit the same heights. Albarn is at his best when he’s plaintive, no more so than on the highlight that is Merrie Land, a hypnotic stream of consciousness that’s the best thing he’s done in years. Likewise, The Last Man To Leave is heartbreaking in its disappointment of modern-day English values (‘we don’t want you anymore’) and the organs and strings evoke the more unsettling moments from their debut.

Damon Albarn’s quality control is remarkable given that this is his third album in 18 months. But it’s also a reminder of the niche that he’s carved out for himself, of a philosophical observer of modern English life. He’s been doing it for nearly 30 years, but not quite as frequently as he once did.

When he does go back to source, he’s untouchable.