Books about bands – and, for that matter, rock music in general – are big business, playing on the compulsive need of fans to know the finer details; to inhabit a space and time in which the songs they so lovingly play on their iPods and car stereos flourished, to take a peek between the ears of the artists who created them.

Books about bands – and, for that matter, rock music in general – are big business, playing on the compulsive need of fans to know the finer details; to inhabit a space and time in which the songs they so lovingly play on their iPods and car stereos flourished, to take a peek between the ears of the artists who created them.

It’s no surprise then that when such books are penned by bands and artists themselves, a more coveted bounty of music ephemera is laid bare.

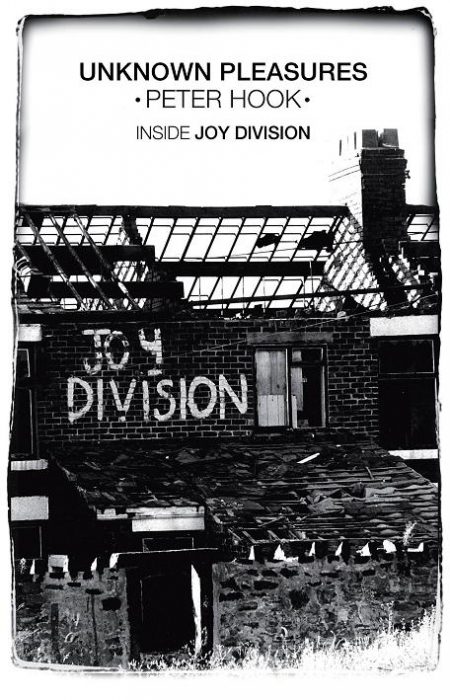

Peter Hook’s Unknown Pleasures: Inside Joy Division is a lucid and unromantic account of the band’s short life and a veritable treasure trove for those aforementioned fans. Between chapters, a detailed timeline is presented, sketching Joy Division’s gigging history and notable events of the period, including the rise of bands like the Buzzcocks and the Sex Pistols, and the goings on at the then-nascent Factory Records.

Hook tells the story of Joy Division with candour and humour, describing how early name suggestions included ‘Slaves of Venus’ and ‘Boys in Bondage’ and how the band combated suggestions that they were Nazi sympathisers (‘We’re not fucking Nazis. We’re from Salford’), a notion given credence when guitarist Bernard Sumner name checked Rudolf Hess during an early gig, and subsequently designed an EP sleeve with a picture of a member of the Hitler Youth banging a drum. ‘There was nothing more to it than a bunch of lads…who were a bit obsessed by the war,’ Hook states.

As well as unflinchingly tackling the history of his band, Hook catalogues his own youth, which included several years in Jamaica (‘Would I have suited dreads and reggae?’), and reveals what first sowed the seeds of a lifelong love of music – ‘when the bug didn’t so much bite as take a huge fuck-off chunk out of my leg’ on hearing Cockney Rebel’s ‘Sebastian’ in 1973.

Of most interest to the band’s devotees, however, is how Joy Division came to be. Chronicling their early rotation of frontmen, and their time as ‘Stiff Kittens’ and ‘Warsaw’, Hooky describes how the stars aligned when Ian Curtis joined the band and how, having seen the Sex Pistols tear through the Electric Circus, they were each determined to inject the same gusto and fervour into their own music.

Of course, the story has been told before; what Hook manages to do is put a new slant on it. Curtis is portrayed as one of the lads, not as the doomed troubadour of myth: ‘He was poetic and romantic and soulful – but he was still a guy in a band and he liked to do what guys in bands do. Which is to cop off with girls and have a laugh’.

A man who enjoyed winding up his bandmates on tour by pissing in their ashtray, asking a local on Rue St. Denis where the prostitutes were so as to satisfy the band’s curiosity, sprinting after a wayward drum that flew from the tour van and rolled down the motorway. In fact, Hook’s contempt for the popular image of Curtis is evident from early on: ‘What gets me sometimes about the deification of Ian is that it suggests a real division between Ian and the rest of the band that in reality wasn’t there’.

Recalling when the group played the Leigh Open Air Festival, he describes Ian’s shared glee at the band discovering, in Hook’s words, ‘the most unbelievable turd I’ve ever seen in my life’ in one of the toilets. ‘Ian didn’t go scurrying off to bury his head in a Dostoyevsky… No, he was laughing just as hard and was just as grossed-out as all of us. Just one of the lads.’

There are references to the singer’s portrayal in film, too – ‘The guy in Control, Sam Riley, played him as being much more arty and conventionally pretty than he was in real life; Sean Harris in 24 Hour Party People had a bit more of the real-life edginess and intensity’, but Hook does not dedicate undue time to peeling back every layer of the singer’s persona. Rather, he describes his own experience in Joy Division, the antagonism between himself and guitarist Bernard ‘Barney’ Sumner, who uncharitably hoarded his sleeping bag when the band were quartered in draughty B&Bs or holed up in their van while on the road, and the unglamorous reality of recording their first and second albums.

Interestingly, there are also excerpts of early reviews, some scathing (‘I found Joy Division’s “tedium” a blunt, hollow medium’ opined Nick Tester in Sounds), some flattering (‘the most physical hard rock group I’ve seen since Gang of Four’ – Adrian Thrills, NME), as well as photographs and an excellent track-by-track analysis of both albums.

Larger-than-life characters like manager Rob Gretton and Factory’s Tony Wilson, meanwhile, flit in and out of the story for light relief, while Hooky’s own memories of being a suspect in the Yorkshire Ripper killings (due to his van being sighted in a succession of red light districts, where the band played small clubs) and fighting with fans raise more than a few chuckles.

The reader is also given a sense of how quickly it all happened for these young men; they did not become overnight stars – in fact, they did not become stars at all – but after a blitzkrieg of gigs up and down the country and within just two years, they had made their indelible mark on the musical landscape. And unlike traditional rock biographies, we get the sense of the musicians as regular folk.

Joy Division did not explode into the public consciousness and reap the rewards of their artistic endeavours. They were a jobbing band who, before fulfilling their potential, imploded with their singer’s tragic demise, a period recounted heroically here by Hook. Indeed, the final passages of the book are truly heart-wrenching.

While he occasionally sounds, by his own admission, like ‘an old fart’ when regularly referring to what it was like ‘back then’ (‘Honestly, kids in bands these days, they don’t know they’re born’ he moans at one point), Peter Hook has written an honest, no frills account of Joy Division in all their troubled, gloomy glory.

Packed with anecdotes and insights, Unknown Pleasures is a rewarding read.